[Feature]

40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

by Soumik Nandy Majumdar

‘As a matter of existence, art aims at the political as the ultimate means of emancipation.’

-Guven Incirlioglu (Xurban Collective)

Anonymous people on the street, faces of deprivation and exploitation, daily hardships of the browbeaten and an unrelenting expression of continual struggle – these are some of the persistent motifs in Suranjan Basu’s art, making him a characteristic example of a socially conscious artist of recent times. Rooted in a social-realist idiom (which was gradually loosing its espousal to the younger generation of artists of his time and thus becoming ‘unfashionable’), Suranjan Basu (1957–2002) was convinced with his motivation and decided to address the ‘socio-political’ head-on. In that sense, he was charting out a path against the grain and the timbre of protest in his art was unmistakable right from the beginning.

Anonymous people on the street, faces of deprivation and exploitation, daily hardships of the browbeaten and an unrelenting expression of continual struggle – these are some of the persistent motifs in Suranjan Basu’s art, making him a characteristic example of a socially conscious artist of recent times. Rooted in a social-realist idiom (which was gradually loosing its espousal to the younger generation of artists of his time and thus becoming ‘unfashionable’), Suranjan Basu (1957–2002) was convinced with his motivation and decided to address the ‘socio-political’ head-on. In that sense, he was charting out a path against the grain and the timbre of protest in his art was unmistakable right from the beginning.

Resentment and protest: art of Bengal in the 40s

Despite the significant thematic shifts brought about by the changing times and altered political configurations, Suranjan’s art connects itself historically to the unique moment in the history of modern Indian art shepherded by a few young artists of the 1940s in Bengal. During that time the likes of Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915–78), Zainul Abedin (1917-76), Govardhan Ash (1907-96), Somnath Hore (1921-2006) and Gopal Ghose (1930-80) felt the exigency to respond to the appalling ground-reality of Bengal in the wake of the devastating Bengal Famine (1943-44) and the traumatic experiences communal riots (1946). In fact, the very formation of the artists’ collective – the Calcutta Group – in 1943, amidst the commotion and peril of the Second World War and the infamous Bengal famine is a testimony of the artists waking up to a call different from the typical Nationalist agendas and Bengal School ‘romanticism’. Historically speaking, the decade of the 40s saw the emergence of a noticeably different mode of artistic expression for a primarily socially-responsive content, which made it a deviant from the dominant narrative of the ‘national’. When in the political sphere the alternative prospect of a Marxist-Communist initiative was on the rise and the concomitant cultural manifestations of the anti-fascist protest movements were catching on, this genre in the art of the 1940s owes itself considerably, directly or indirectly, to the evolving transformation in artistic consciousness. This transformation could be read, in the art of these artists, as a voice of dissent. They all disagreed to ‘imagine’ a nation and felt the necessity to address the immediate and the ‘real’ as more pressing and pertinent. Irrespective of whether one was working from within defined parameters of a particular political agenda or not, all the above artists held art as a tool to answer to the ‘needs of the time’. Clearly, for them the ‘needs’ were the urgency to communicate the concern for the suffering multitude. The element of ‘protest’ – political or otherwise – can be located in this indomitable urge and the search for the relevant visual idiom and format to fulfill that urge as a social mission for the artists.

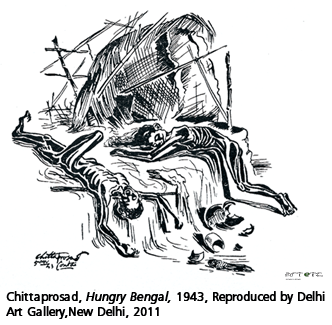

For artists like Chittaprosad, Zainul and Somnath, stark ‘black and white’ drawings of the chosen/observed reality are moving records of a dismal situation socially engendered by means of exploitations and coercions. Their political affiliation with the Communist Party and subsequent exposure and experience of the harsh reality helped to infuse their art with an unflattering mode of depiction often with a directness of a protest-slogan. It is noteworthy that pictures of Zainul Abedin, Chittaprosad and Somnath Hore had a wide circulation in the city and their sketches were regularly published in the periodicals like Janayuddha and People’s War published by the Communist Party. Under these circumstances and with an entirely new approach to the function of art, the very artistic practice became synonymous with documentation or eye-witness account of the life of the wretched masses. A path-breaking work in this context is the publication of Hungry Bengal (November 1943) – a textual and visual record of Chittaprosad’s travels through the famine and cyclone ravaged district of Midnapore, south of Bengal. Both the text and the drawings reveal the grimness of the situation and the images particularly focus on the deplorable condition, by drawing attention to specific details. Animals and birds feasting upon the human corpse, broken pots scattered in a devastated hut, pathetic vacant expressions of the hapless people – are some of the poignant details Chittaprosad pays attention to in these images. In doing so he privileges the socially concerned and politically charged ‘documenting’ function of art over both academic traditions of art school and the Bengal School gharana. It is noteworthy that right away Hungry Bengal provoked the wrath of the government and subsequently the British authority confiscated and destroyed five hundred copies of this book. The power in question simply could not tolerate a book like this !

For artists like Chittaprosad, Zainul and Somnath, stark ‘black and white’ drawings of the chosen/observed reality are moving records of a dismal situation socially engendered by means of exploitations and coercions. Their political affiliation with the Communist Party and subsequent exposure and experience of the harsh reality helped to infuse their art with an unflattering mode of depiction often with a directness of a protest-slogan. It is noteworthy that pictures of Zainul Abedin, Chittaprosad and Somnath Hore had a wide circulation in the city and their sketches were regularly published in the periodicals like Janayuddha and People’s War published by the Communist Party. Under these circumstances and with an entirely new approach to the function of art, the very artistic practice became synonymous with documentation or eye-witness account of the life of the wretched masses. A path-breaking work in this context is the publication of Hungry Bengal (November 1943) – a textual and visual record of Chittaprosad’s travels through the famine and cyclone ravaged district of Midnapore, south of Bengal. Both the text and the drawings reveal the grimness of the situation and the images particularly focus on the deplorable condition, by drawing attention to specific details. Animals and birds feasting upon the human corpse, broken pots scattered in a devastated hut, pathetic vacant expressions of the hapless people – are some of the poignant details Chittaprosad pays attention to in these images. In doing so he privileges the socially concerned and politically charged ‘documenting’ function of art over both academic traditions of art school and the Bengal School gharana. It is noteworthy that right away Hungry Bengal provoked the wrath of the government and subsequently the British authority confiscated and destroyed five hundred copies of this book. The power in question simply could not tolerate a book like this !

The abbreviated realism zooming on to harsh details was also shared by Zainul Abedin and to an extent Somnath Hore. Hence, the protest was not only of a socio-political kind but importantly it left serious consequences in the art idiom. It was, in the words of Sanjoy Kumar Mallik, ‘an attempt to purge art of its mythic, classicized, literary and lyrical material made possible … by concentrating on the image of a suffering and debases humanity.’1

Zainul Abedin in his harsh images of the urban destitute visualized in the most rudimentary starkness of black ink employed by dry-brush technique successfully did away with tonal softness usually associated with romantic view of life. Whereas Chittaprosad often inscribes the names of the suffering people on drawings, Zainul emphasizes the anonymity of the sufferers and the ignominy of the starvation and deprivation. Besides having their drawings printed in the party periodicals the Communist Party even organized an exhibition of Zainul’s drawings in 1943. Beyond doubt, they left no stone unturned in ensuring the accessibility of these pictures to the mass. Thus any kind of exclusivity was opposed and art was made ‘public’ in the most elementary sense of the term.

Bengal Painters Testimony (1944) – an album of pictures published on the occasion of its eighth Annual Conference by the All India Students’ Federation – is another such attempt to make socially relevant art to the public and this album we find two touching famine drawings by Gopal Ghose. Ghose’s imagery may not be politically charged yet the resentment and a sense of accountability is evident. He turned to the imageries of a riot-torn city as a theme with equal vigor and exigency. The violent flames and burning vehicles which changed the cityscape during those dreadful days found a compelling expression in Ghose’s paintings. Similarly, Quamrul Hassan engaged himself with the appalling visuals of famine with the goriest details. Haunting memories of history got inscribed in Quamrul’s art conveying in the language of illusionist realism the severity of the intolerable disaster.

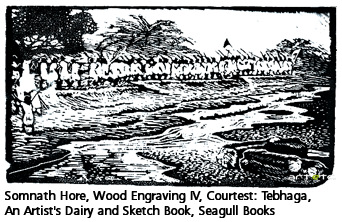

In 1946 Somnath Hore took up the project of a visual documentation of Tebhaga movement in North Bengal when he was still a second year student in the Government School of Art, Calcutta. Tebhaga Diary and the subsequent Tea Garden Diary (1947) eschew the rhetorical slant evident in Zainul’s drawings and tend to become more factual. The very act of recording through sketches (and later in wood-engravings) one of the strongest ‘left-wing mobilizations of the politicized peasantry in Indian history’ was another testimony to the political consciousness of these artists and their conviction in the potentiality of art to voice the revolutionary masses. In Somnath’s Diaries what is most significant beside the visual facts is his conviction in the struggle of these suppressed men and women and their political aspirations. Amidst the abysmal situations caused by the man-made famine Somnath found the sharecropper’s revolt reassuring and heroic. Consequently his images are affirmative and determined, moving away from the earlier images of suffering to a new image of conviction – political field notes assuming the status of a political vision.

The visual forms of protest found a more convenient and explicit voice in the captivating posters designed by Chittaprosad. These propaganda posters he did for the party are clear-cut in content and taking recourse to the satirical mode merged with an anatomical precision are strong visual statements of conviction and dissent. The rebellion character of art is nowhere as pronounced as in these works, often reminding us of Gaganendranath Tagore’s cartoon in terms of its uncluttered directness and rancor. In this context, the function played by the technology of printmaking is enormously significant. Zainul Abedin, Chittaprosad, and Somnath Hore were amongst the first few to realize the potential of printmaking as a medium for the masses, and led by Chittaprosad, printmaking certainly assumed a new role as an instrument of protest.

In the process of articulating the experiences, responses and engagement with the immediate social reality often with an unequivocal political commitment, these artists of the 40s in Bengal, for the first time to the history of modern Indian art, provided with a promising iconography of protest. The fact that it still moves us intensely (the recent retrospective show of Chittaprosad in Delhi and Kolkata is an evidence of that) is a confirmation of the enduring power of this language of protest no matter how brief and fleeting the moment was. This is perhaps due to the underlying humanitarian concern that has kept these artists engaged throughout the ouvre.

Suranjan Basu: continuance of the legacy

Born almost two generations later Suranjan believed that ‘art is politics’. He reacted to the social incongruities engendered by the exploitative capitalist forces, responded to the ugly realities of contemporary life and was peeved at the repulsive display of wealth by the upper classes in contrast to the abject poverty of the slum dwellers. This sense of social realism was certainly political, developed as a reaction against escapist idealism and self indulgent romanticism. His commitment to the values derived from this responsiveness remained undiminished throughout.

Suranjan was also aware of the flipside of this position. He knew that simplistic political equations often mask a far more extensive and urgent confrontation – political as well as aesthetic. Hence he engaged himself with the problems of artistic methods as enthusiastically as with the subject matter of his art. The expressionistic treatment of the faces done during 1980-81 while he was still a student in Baroda was the early signs of his attention to human plight and artistic problems of technique, at once. Their blank yet snooping stares defy any sort of naturalistic rendering; they correspond rather to the character peculiar to the medium itself, which is woodcut – Suranjan’s forte. These faces seem to be conglomerations of various kinds of textures and tool-marks subject to the planes and different segments of the faces. He does not adhere to the academic realism so well adopted by the 40’s political artists. Suranjan takes an effectual shift. In his art, known people, owing to the character of woodcut assume an impersonal identity in the angst ridden expressionist idiom vis-à-vis the medium. When one scans his entire, short lived but prolific, oeuvre, one finds that he has handled each and every medium with equal élan. Suranjan realized early in his artistic journey that an appropriate language for his art would emerge as much from the given medium as from the reality out there. Right at the outset he struck a visual ambivalence between the nature of the subject and the quality of the medium, later proved to be very vital for his work.

Suranjan was also aware of the flipside of this position. He knew that simplistic political equations often mask a far more extensive and urgent confrontation – political as well as aesthetic. Hence he engaged himself with the problems of artistic methods as enthusiastically as with the subject matter of his art. The expressionistic treatment of the faces done during 1980-81 while he was still a student in Baroda was the early signs of his attention to human plight and artistic problems of technique, at once. Their blank yet snooping stares defy any sort of naturalistic rendering; they correspond rather to the character peculiar to the medium itself, which is woodcut – Suranjan’s forte. These faces seem to be conglomerations of various kinds of textures and tool-marks subject to the planes and different segments of the faces. He does not adhere to the academic realism so well adopted by the 40’s political artists. Suranjan takes an effectual shift. In his art, known people, owing to the character of woodcut assume an impersonal identity in the angst ridden expressionist idiom vis-à-vis the medium. When one scans his entire, short lived but prolific, oeuvre, one finds that he has handled each and every medium with equal élan. Suranjan realized early in his artistic journey that an appropriate language for his art would emerge as much from the given medium as from the reality out there. Right at the outset he struck a visual ambivalence between the nature of the subject and the quality of the medium, later proved to be very vital for his work.

Thus he sustained a dual commitment – to his social concern and to his medium, to his subject and to the making of his art, with equal sincerity and concern. He continually expanded the scope of his art by allowing an ever increasing space for subjectivity. And this was integrally connected to his passion for the process of image-making. Charmed by and armed with the immense possibilities of print-making, be it lithography, intaglio, linocut or woodcut, he delved deeper into the problems of representation itself, thus expanding the scope of subjective interventions.

In the lithography titled Shop Dismantling Suranjan rather candidly responds to the experience of drawing on a litho stone with a conte´ and achieves a remarkable spontaneity. The general result is evident in the dynamic execution, abrupt strokes and tonalities of the conte´ and the restlessness of searching lines. It also echoes the suddenness of such an event when unguarded struggling people are abruptly and forcibly thrown into a bleak hapless future. Similarly, in his woodcut series’ like Men on the Street, Sketchy History and History Desired, History Lived Suranjan tries to attain a liaison between the medium and the theme. The rugged drawings and sharp angularities of the contour lines introduce a kind of energy into the image, making the picture strikingly lively. Often, in terms of a more obvious visual allusion, this kind of treatment in his works suggests the harshness of life and the ceaseless survival battle fought every moment by these people.

Critical realism and moments of exhaustion

In most of his images carrying a hint at a narrative allusion Suranjan attempts at transcending the temporality of a condition empowering it with a wider political inquest. This is what he does in works like Sketchy History and History Desired, History Lived. He salvages the images from getting consumed in the mundane. Yet, it is in the mundane, in the daily life, that Suranjan finds his concerns inscribed. As Suranjan is aware of the risk of hamming, he culls his gestures and postures not from a given stock of much used symbols (of protestation for instance), but from his own observed reality. The commonly shared language of gestures too is harvested from this experiential world. Still, the timeless iconic timbre of his works may convey something mistakenly opposite. It may make the oppressed people look like an unchanging element in the society. It may betray a sense of resignation to status quo and in that way fall short of a political will within the imagery. Though to some extent Suranjan’s works can still disturb us in our contentment and leisure, they usually address the vulnerability of the people represented; they hardly address our helplessness or in other words our political inadequacies. Probably Suranjan has tried to answer this crisis too. In the series Star Wars and History Desired, History Lived, he does not hesitate to introduce symbols and banner pertaining to a specific left political party, as a likely agency to redress the dismal condition of the downtrodden.

I presume Suranjan believed that a transformed world was theoretically possible and the necessary forces of change could already be recognized and expressed. His party allegiance rather than the artist in him expressed the forces of change in some of these images. He knew that these works were slipping into propagandist mode but he probably meant it that way. But what is more problematic for me is that in this approach art obfuscates the larger complexities of political scenario and fall prey to reductionism and exclusivist trap. In such a situation the pre ordained tenets of party ideology absorbs all the attentions; the complex issues of exploitations and power equations get marginalized, and at times, rather paradoxically many of such images get depoliticized. Perhaps Suranjan too felt this inadequacy. Bahurupi is such an example from the series Star Wars. Here, the two bahurupis can be seen in their most unguarded and true self, taking a small break from their hectic profession while their painted bodies and the animal mask linger as the only witness to their silent pains of double life. The conviction embedded in this composition will remain powerful than any political rhetoric. Suranjan discovers such potential moments of unspoken pathos also in light hearted compositions on subject matters such as the local jatra troupe, the makeshift dressing room or simply two men waiting.

While the trivialities now come up as probable subject matters, he also begins to take a tongue-in-cheek look at different preposterous conventions within the prevailing socio-political framework. Angutha Chhap is a curious result of this approach. Emulating (read mocking) the style of popular Kalighat prints Suranjan here is no more in the mood of documenting but visually commenting with an intention of ridiculing an accepted system. He, on the sly, pokes fun and tries to puncture the inflated ego of democracy. Satire creeps in. Strategically, satire opens up for Suranjan a whole new set of possibilities to articulate his social concerns and the voice of protest in an unusual way.

Rhetoric and the concern

“I am more active with a sort of a political activity and I try to mix for my political activity my experience with my art and therefore many times my works become like, as if I use it as a political tool.” (Quoted from ‘Suranjan Basu in conversation with Subba Ghosh, Khoj 2001’)

Overtly rhetoric as this declaration may appear, it speaks volumes on Suranjan’s particular kind of attachment to his art. At one time there was this widespread assumption that art can level out social anomalies, that it can potentially assume the role of a ‘political tool’. Even if this supposition appears to be dated and highly questionable today it has serious implications in the history of art and it has been a debatable topic all through. But for an artist, committed to a specific kind of political agenda in art, the urgency of this issue is of a different nature. The artist seeks an answer. The protest art of the 40s in Bengal and emerging again in the art of someone as prolific and committed like Suranjan Basu in the 80s, loudly or quietly, is always seeking an answer in tandem with a changing consciousness in human dignity and labor. The value of protest art, despite its rhetorical tendencies lies in upholding them with a sense of urgency.

Reference

1. Sanjoy K. Mallik, Chittoprosad – A Retrospective, vol.1, p.39, Delhi Art Gallery, New Delhi, 2011.

Tags: art